This article is also available in PDF format.

|

An exploration into the mystery of the empty large granite coffers found in an Egyptian underground tunnel, officially part of a larger complex of tunnels called the Serapeum where Dynastic Egyptians buried their bulls; and my own interpretation. Contents: 3. Descriptions from Auguste Mariette, the Serapeum's discoverer 4. Why the Granite Coffers are from Another Older Civilization |

|

There is so little information available about the Serapeum (a place to bury embalmed bulls) in Saqqara, in Upper Egypt. Archaeologists don't seem to be interested in it. Maybe because there is one underground gallery that doesn't fit into their established theories of the Dynastic Egyptian history, which can not be older than 3000 B.C. It is my opinion that the Main Gallery with its granite coffers dates from Atlantean times, more then 12,500 years ago. I have looked around on the internet and gathered the little information available about both the Main Gallery and the later smaller galleries. The present official statement is that they were all used as a Serapeum, but on closer inspection only the smaller tunnels were used as the Serapeum. |

|

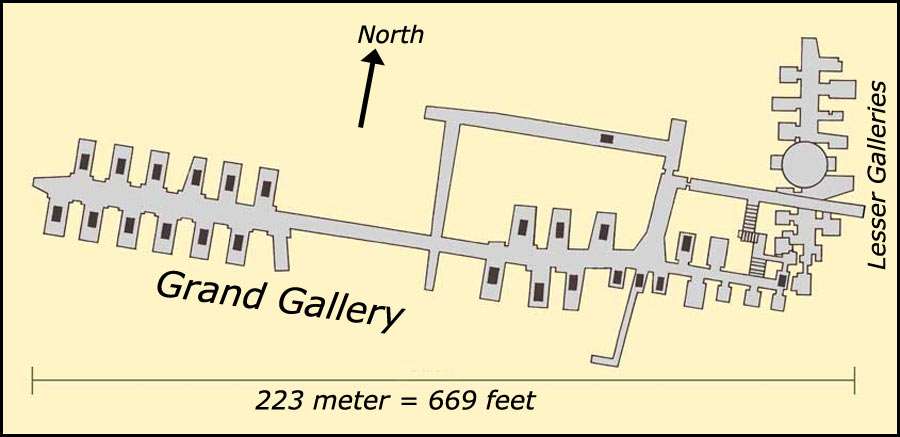

1875 Engraving of the Main Gallery. |

Main Gallery in 1855 |

|

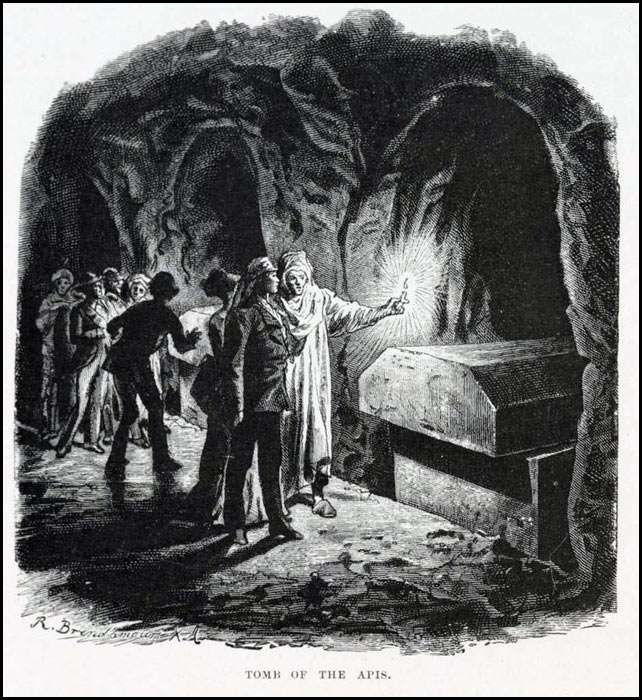

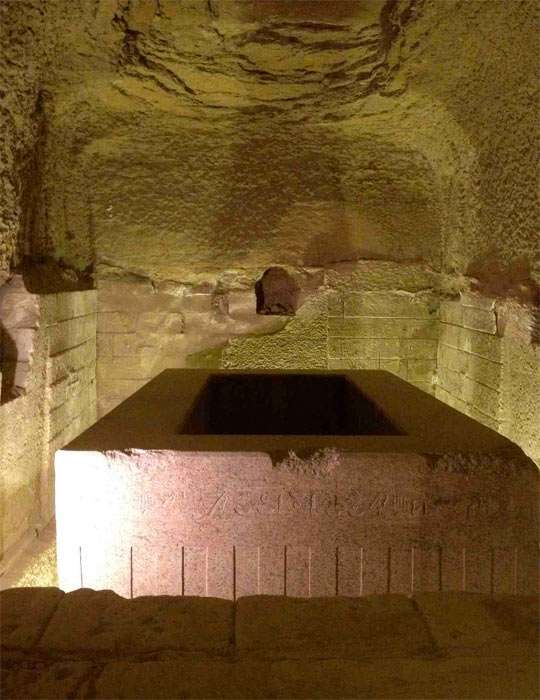

The Serapeum is the name given to the underground galleries, situated to the north-west of Zoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara. The are underneath a temple, and the main entrance to the tunnels is at the end of an avenue of sphinxes. It was discovered in 1851 by French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette. Restoration of a part of the galleries took place in the late 1900's and early 2000's, during which the Serapeum was closed. After extensive restoration work the Ministry of Antiquities have finally opened the door to part of the underground galleries in 2012. The official explanation is that all the galleries were once used as a Serapeum, that is, a burial place for sacred bulls. That is actually an incorrect statement, as we will see, based upon the records of their discoverer. The so-called Lesser Galleries were indeed used for the burial of the bulls, but the Grand Gallery was not used as such, in contrast with the repeated claims of archaeological authorities. |

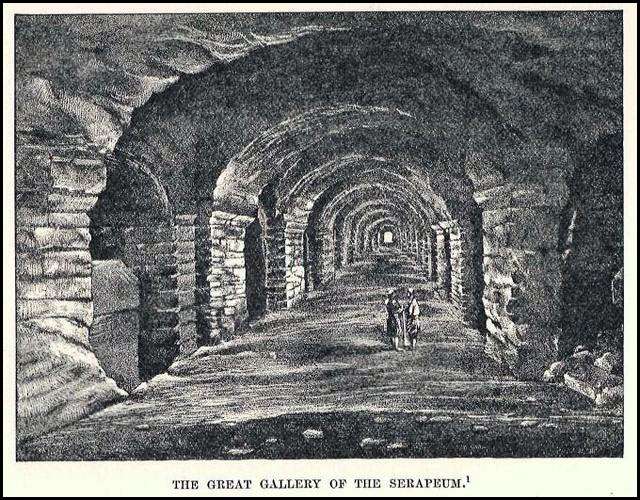

Map of the underground tunnels.

|

There is a big difference between the Grand Gallery with its huge granite coffers which bear all the hallmarks of a highly sophisticated technology, and the Lesser Galleries with its primitive tunnels and small wooden sarcophagi. The Grand Gallery has large side-chambers, or niches, and contains 24 huge granite 'sarcophagi' shaped from single blocks of stone, each weighing between 60 and 80 tons. Archaeologists didn't know what they were used for and postulated the theory that these were also sarcophagi for embalmed bulls. Embalmed bulls were found in the Lesser Galleries inside wooden sarcophagi, and it was assumed that the granite coffers once also had bull mummies in it which were taken out by robbers at a later time. This is the official explanation for the existence of the granite coffers. When Auguste Mariette entered the tunnels in 1850 he found that the granite coffers in the Main Gallery were empty but the lesser vaults were still intact with all the mummies and numerous artifacts still present. So, clearly, no robbers had been inside the tunnels. At the time when the tunnels were used as a Serapeum, the Egyptians did not use the granite coffers for their bull mummies. The Grand Gallery and its coffers were already there from more ancient times, and the Egyptians from the Dynastic times left the coffers for what they were. After all they were way to big to serve as a sarcophagi. They might also not been able to move the 20 ton lids around either. |

The Grand gallery at earlier times. |

The Grand Gallery today after renovations. |

3. Descriptions from Auguste Mariette, the Serapeum's discoverer

Picture is from Isida Project website.

In this article I have used the same numbering system for the coffers.

Only the Grand Galleries, and side tunnels are shown here, not the Lesser Tunnels.

|

Looking around on the internet, I have not been able to find any document from archaeologists who might have examined the Grand Gallery and the granite coffers, or of the Serapeum in its entirety. The only document I found was an 1882 book Le Sérapeum de Memphis, by professor G. Maspero, Professeur de College de France, Directeur Général des Musées d'Egypte, who republished the original manuscript of Auguste Mariette who discovered the Serapeum. Luckily I can read French, so I went through the chapters that dealt with the underground tunnels. Mariette writes that when he discovered the main gallery with the 24 granite coffers, that these were all sitting in niches of which the vaulted roofs have collapsed and the stones were laying all around and on top of the coffers. The lids of the supposed sarcophagi had all been moved slightly and stones had fallen in. The gallery and vaults had been cut out of the fragile limestone underground, and the amounts of fallen and broken stones were sometimes so numerous that it was difficult to access certain areas. He didn't find any archaeological treasures here. The granite coffers had not been used to bury any embalmed bulls. |

One of the granite coffers in a niche, in 1878 |

The same granite coffer today. |

| Mariette found 22 of the coffers placed in the middle of their niches, and one coffer (#26 on the map) left behind in one of the other galleries. One (#4) was placed in the end of one of the galleries that led to one of the four access gates (at the surface) of the underground tunnels. He estimated the dimensions of the coffers as 3.30 meters in height, 2.30 meters wide and almost 4 meters deep. |

|

Coffer #26 left behind in a tunnel. |

Coffer #4 at the entrance of another tunnel. |

|

In the very beginning of the gallery he also found numerous inscribed steles from the Dynastic times. A stele is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected as a monument, very often for funerary or commemorative purposes. |

|

The beginning of the Grand gallery where the steles were placed (now removed). |

|

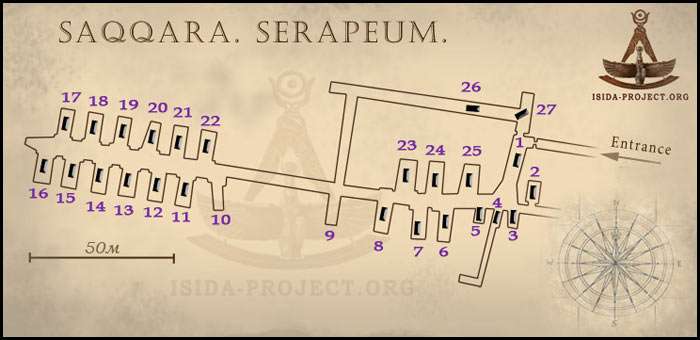

The Lesser Tunnels were clearly inferior to the Main Gallery, but they yielded numerous treasures. They were built mainly at a right angle to the first gallery. Auguste Mariette: "The new tunnels, which we have called "the Little Tunnels", the name of Large Tunnels leaving to the ancient ones, do not have the regularity, the greatness and the conservation of the others." The Little Tunnels had a wealth of steles, vases, statuettes, and fragments of wooden coffins, but all in disarray. The Lesser Tunnels were also far more damaged, and the vaults had crumbled to pieces. Somewhere in the middle of the tunnels the entire roof had collapsed at some time. That is where they found an intact mummy in a wooden sarcophagus. The mummy had a mask, amulets and jewels. Mariette also found an Apis (=bull) tomb but with the mummy of a man in it. |

|

The Lesser Tunnels with a sarcophagus still in. Photo taken during restoration in 2008. Notice this sarcophagus is very much smaller than the granite coffers in the Main Gallery. |

One of the Lesser Tunnels, at the entrance gate. |

|

Mariette: "In the Grand Gallery the steles do not extend further than four entrance gates as if the funeral visitors could not go or were prevented further into this gallery than just a few meters. In contrast, in the Lesser Tunnels, steles are found over the entire length of the gallery, from the entrance all the way to the end." Aside from these galleries, he also found isolated vaults and tombs. Linant-Bey (I guess he was a friend of his) measured one of the granite coffers in the Grand Gallery, and estimated the weight thereof as 65 tons. Mariette wondered how the ancients were able to transport such a weight into the galleries and place it into the vault without the help of our modern technologies. The galleries are only four to five meters high, but the vaults are seven to eight meters high because they are two to three meters lower than the floor of the galleries. That would be an immense problem lowering such a heavy weight down a kind of stairway or slope. Maneuvering the large coffer is not an easy task because there is not enough room in the narrow vaults for a large number of people wooden constructions. One wonders why the builders made a deep sunken floor in the vaults, making it so much more difficult for the very heavy coffers to move into? Why was this sunken floor important? |

4. Why the Granite Coffers are from Another Older Civilization

|

The official explanation given by the Egyptian authorities and archaeologists is that the entire complex was a Serapeum. The Lesser Tunnels were full of bull mummies, a couple of human mummies and plenty of artifacts like steles, vases, jewelry, statuettes. The fact that the large granite coffers in the Grand gallery were empty is explained by the authorities as robbers who took the bull mummies out of the coffers at one point in time. This is in contrast with the facts, and here is why. All the tunnels are connected, and when Mariette discovered the site in 1850, everything was undisturbed. All the valuables were still there. No robbers had ever entered the tunnels. Why was the Grand Gallery empty of bull or human mummies? Because the Dynastic Egyptians themselves had discovered this ancient tunnels, but they did not use it, or the granite coffers therein, to bury anybody. The walls of the Lesser Tunnels were full of steles, but in the Grand Gallery the walls have only a few steles at the very beginning. It is as if they had the intention to use the Grand Gallery but gave up on it. |

|

The Grand Gallery and its granite coffers were already there when the Dynastic Egyptians discovered it. They thought about reusing what they found, but they changed their minds. Then, they dug their own tunnels for the burial of their sacred bulls. So, what speaks against the official theory of bull sarcophagi made by Dynastic Egyptians, and for an advanced technological civilization that was much older? The hardest stone available Why bury a bull in a stone coffer made from very hard rock? The Isida Project project lists the following stone identification for the coffers. Most of them were made from different kinds of granite. Some were made from gabbro-diorite, granodiorite, syenite porphyry, and diorite. They are all 6 to 7 on the Mohs hardness scale. That means that they were all really hard and durable rock. They also allow for very smooth and shiny polished surfaces. As we have seen this seems to have been very important for the interior surfaces of the coffers. Although the Dynastic Egyptians would have been able to quarry granite blocks by splitting the rock, cutting the granite in rectangular block with level, flat surfaces can only be done with circular saws, or rope saws, made from at least hard steel, which they didn't have. The hardest metal the Egyptians had was iron, which was slightly harder than bronze. Their iron tools were still soft because they couldn't reach the temperatures to harden the iron. Even today cutting granite is very difficult. The basic machines that are used for cutting and polishing granite are saws, polishers and routers. Most granite blocks taken from the quarries are cut into slabs of varying widths by modern circular saws with industrial diamond tips. Diamond wire saw also has become increasingly popular these days for cutting granite. Diamond wire saw machines have commercial diamonds fixed on the wire. Diamond being hard makes the job much quicker. Slabs of granite are polished by special machines that use either large metal discs or abrasive bricks made from silicon carbide. Silicon carbide is a modern synthetic compound of silicon and carbon mainly used for its extreme hardness. The creators of the coffers choose granite and other rock of similar hardness because they were able to mine, cut and polish these hard stones with ease and with precision. They had advanced technology that they used worldwide, because we find similar examples of cut and polished multi-ton stones from ancient civilizations all over the world. |

|

Too expensive and too big for a bull mummy The Egyptians had not the means to fashion a huge granite coffer to the precision that the coffers in the Grand Gallery have. They also would not move around a 100 ton granite block from a quarry 1000 km away on wooden rollers, in the sand. Not to mention to lower it into tunnels and maneuver it around into a small niche, where there is sometimes not even enough space between the wall and the coffer for a man to stand. Just to bury a bull in it? Why make a lid that weighs 20 tons? As we have seen, they buried their embalmed bulls in wooden coffins in the smaller tunnels. Much, much easier! The granite coffers are also way oversized for a bull. Cutting, shaping, grinding and polishing a granite coffer is time consuming and expensive. If you make a sarcophagus you make it to just fit the mummy in. Any extra space is just wasted. You also don't polish the inside of the coffer to a brilliant smooth finish. Even the pharaohs were never buried in something that big. I have measurements for three coffers. One is from Linant-Bey given to Mariette who added it in an addendum in his publication. The outer dimension of the coffer is 3.85 meters long, 2.32 meters high and 2.32 meters deep. The inner dimension is 3.17 meters long, 1.73 meters high and 1.46 meters deep. The lid is 3.85 meters long, 0.92 meters high and 2.32 deep. The combined weight he calculated is 62 tons. The Isida Project gives dimensions for two coffers: Coffer#2, which doesn't have a lid: outer dimension are 3.8 m x 2.5 m x 2.4 m Coffer#17: outer dimension: 3.8 m x 2.17 m x 2.3 m. |

|

A little Photoshop to compare sizes of a bull (which is about 2.3 m long) and a coffer based on measurement by Linant-Bey. This is a typical bull mummy from the Dynastic times. |

|

|

Machined precision The coffers have 90 degree edges inside and outside. Especially the inside corners, being 90 degrees in three dimensions is a major feat of technology. Christopher Dunn, who has measured the coffers with precision instruments, contacted four precision granite manufacturers and could not find one who could replicate the perfection with which these granite coffers had been made. The surfaces of the sarcophagi that Dunn was able to examine are perfectly flat. He found that both the coffers and lids are perfectly flat. With its heavy lid in place, the air between the two stone surfaces of a coffer was pushed out, producing an effective seal. The technical difficulties of producing both a lid and a sarcophagus to fit in this precise way are great and more difficult than producing the flat surfaces of the sarcophagi. Christopher Dunn found that the inside of the coffer were so level that they their accuracy was within 0.00005 inch, or 0.00127 mm, at least at the length of the gauge which was 14 inches long. he also found that the radius of the corners was very small: 5/32 inch, or 4 millimeters. Why was it necessary to the builders to create such a flat surcease and such a sharp edge inside the coffers? People from the Russian website Isida Project have also examined the stone coffers, and have found that the outer surfaces were not always perfect. They were sometimes damaged and polished over. However the interior surface, inside the coffers, were always perfect, level and smooth to a high degree, suggesting that it was the interior surface that was extremely important to the creators of the coffers. One wonders why? Not to bury something in it that would never see the day of light again, but rather because it had to be functional to something we are still puzzled about. |

|

Polished, level, flat surfaces inside the coffers.

|

Perfect right angle corners and level surfaces on the inside of the coffers. Picture from the Isida Project |

|

The multi-ton lids Why make something with a lid that weights 15-20 tons? I don't see the primitive Dynastic Egyptians move a 20-ton lid in such a confined space, let alone a much bulkier and heavier coffer. There is just not enough room to built a wooden/rope construction strong enough to move and lift such heavy weight in there. Unless the original builders had an anti-gravity device. The official explanation that robbers moved the lids to get the bull mummies out is totally incredible. When Mariette discovered the underground tunnels, there was only one coffer that was still closed. Mariette (being an archaeologist he was the modern version of a tomb raider) was not able to remove the lid, because after all human hands just cannot push such a heavy lid aside. Mariette had to resort to explosive to blast open one of the sides of the coffer. Any tomb raider in the past would also not have been able to push open the lids. Robbers are poor people, and don't have expensive equipment to move heavy weights. |

Why was it necessary to have such thick and heavy lids? Compare it size with the person next to it. |

|

Functional features I think the coffers were made to be functional. For what we cannot even guess, but there are some indication. We have seen that the interior was very important because this was cut very precise, with sharp corners and the walls were highly level, smooth and polished. Was a mirror-like finish important for the reflection of light waves or sound waves? The lids are very thick and heavy for just covering a coffer. Was this necessary because they were moved on and off frequently, and thus they had to be thick to prevent breakage? Why were the lids not just plain rectangular slabs. This would have been much easier to deal with and it would take less time than fashioning them with slanted or angled sides. The lids do not have all the same shape. The angles and sides differ from one to the other. The shapes seem to have been fashioned that way intentionally. One lid has two notches sharply cut out at the underside of the lid, at both sides, as if something once fitted into those notches. Another lid (#1) has a bump sticking out one side of the lid. This was clearly done on purpose. Similar bumps sticking out of stone blocks are also present in temples and buildings, not only in Egypt but also in the ancient building of Middle America. In my opinion, a feature like this allows the tapping of energy that is present in the stone. Coffer#2 has window-like recesses cut into the sides. The coffers were placed in a sunken floor, one to two meters deep. They would only do this if it was really necessary, because it makes it very difficult to move a 60 ton coffer into a very small niche with no room to maneuver. Unless, of course, if they could make the coffer weightless, and float it in, and subsequently lower it, that would make it very easy. Each niche has a recess in the left and one in the right side of the walls. These were put there on purpose, probably to hold something else. Maybe a clamp from one recess to the other over the coffer to keep the lid down? Or did some technological devices placed in these recesses? |

|

Very smooth, level, polished surfaces at the inside of the coffer, with sharp edges and 90 degree angles. |

Heavy, thick lids to prevent breakage because they had to be removed frequently? |

This lid has two notches cut out of the side of the lid. |

Lid#1 has knobs on the side. |

Coffer#2 is 2.5 meters high. Look how deep the made the sunken floor. Why was this necessary? |

In the left wall you can clearly see the arched recess. The same in the right wall, where they now put a light. |

|

An attempted salvage operation Because the galleries were all undisturbed when Mariette found them in 1850, the granite coffers were not plundered of their supposed embalmed bulls. The lids must have been moved in ancient times, probably in the time of the ancient builders. Maybe, because of the worldwide catastrophes at the end of the Atlantean time (12,500 years ago), these people decided the remove the content of all the coffers, and left the coffers open, except one which they closed again; or maybe there was nothing in it to begin with. Maybe they all popped open by a tremendous earthquake? Maybe it also explains why coffer#26 with its lid#27 was removed from a niche, but left in another gallery. Did something happen that interrupted a salvage attempt? Another lid (#1) lies just around the corner in another gallery, probably from the nearby lid-less coffer in niche#2. Also coffer #4 sits at one end in a gallery, probably also left behind when trying to move it out. Coffer #4 might have come from the east side of the Main Gallery where there are several empty niches. Maybe some of the coffers had already been moved out. In my opinion, the ancients were engaged in a hurried salvage operation. What was in the coffers was removed. Inside each niche, on both sides of the coffers, there is a recess in both the left wall and right wall, as if something had stood there. Whatever it was, it was also removed. Then they were in the process of the removing the coffers themselves. Some were taken out of the tunnels, leaving empty niches in the east end of the gallery, and two coffers were left behind in the tunnels when something catastrophic happened, putting a definite end to their salvage operation. |

|

Coffer#26 left behind in one of the tunnels. |

Lid#27, probably from the coffer#26 lies just around the corner. |

Lid#1 left behind in tunnel near entrance. It probably came from coffer#2 around the left corner. |

Coffer4 left behind at one end of a tunnel. |

|

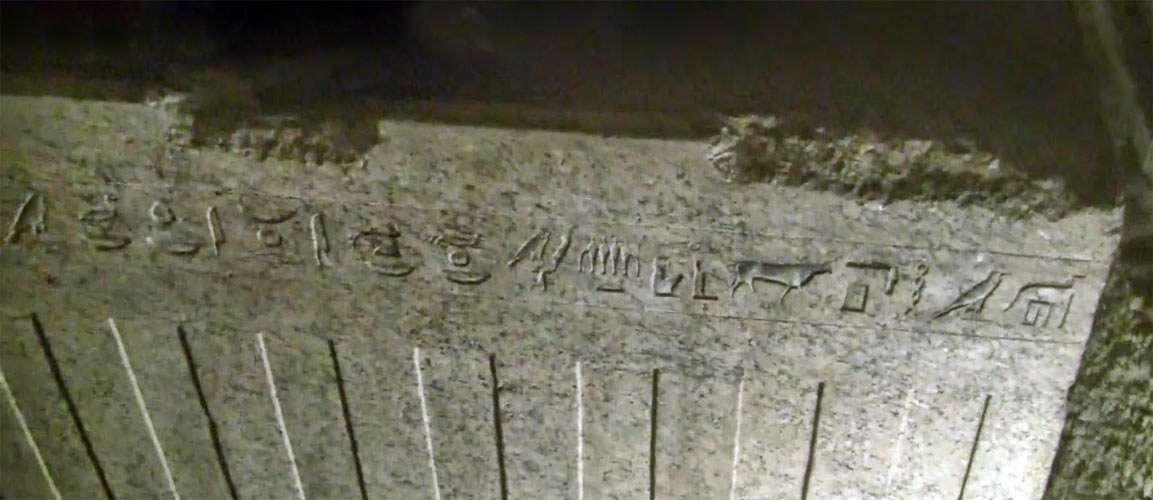

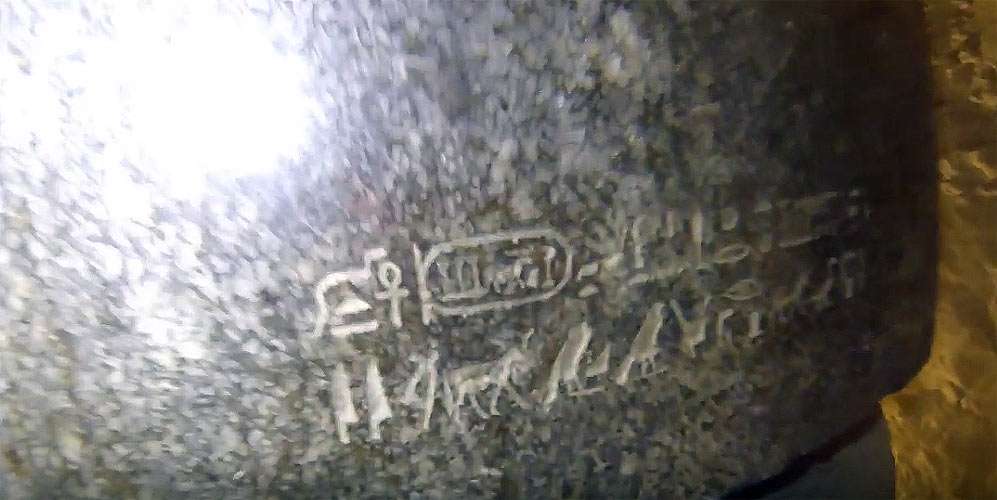

The hieroglyphs: an attempt to falsify their antiquity? I find it strange that Mariette in his Le Sérapeum de Memphis does not mention that some of the granite coffers were inscribed with hieroglyphs. Of the 24 stone coffers only three bear any inscription, and they contain the names of Amasis (XXVIth dynasty), Cambyses and Khebasch (XXVIIth dynasty). This was around 500 to 400 B.C. When you look closely at those hieroglyphs, it becomes immediately obvious that they were poorly scratched into the hard granite, with uneven lines, as if they were made by an amateur. Surely some archaeologists have read and translated them, but I have been unable to find any translation of these texts. I sometimes wonder if they have been made in modern times to make it look that the highly technological made coffers were the product of primitive Dynastic Egyptian who wanted to bury their bulls in it. It wouldn't be the first time that proof of a one very advanced civilization was denied, covered up or just disappeared. Multi-ton granite boxes are difficult to hide, so why not claim that they sarcophagi for bulls? The Egyptian only had bronze and iron tools. Iron is the same hardness as bronze, and both are too soft to work on granite. |

|

Coffer#17 with poorly written hieroglyphs barely scratched into the highly polished surface. |

Coffer#17: wavering lines, and hieroglyphs scratched into the stone. |

Coffer#2 with a line of hieroglyphs going around. |

Two lines of hieroglyphs on the lid of coffer#4 |