back to Spontaneous Human Combustion

|

Historical cases of spontaneous human combustion, with some reviews and analysis in old documents. |

|

Some cases mentioned in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 1836 |

|

From Philosophical Transactions, 1668: An Extract, by Mr. Paul Rolli, F.R.S. of an Italian Treatise, written by the Reverend Joseph Bianchini, a Prebend in the City of Verona; upon the Death of the Countess Cornelia Zangari & Bandi, of Cesena. To which are subjoined Accounts of the Death of Jo. Hitchell, who was burned to Death by Lightning; and of Grace Pitt at Ipswich, whose Body was consumed to a Coal.” This article appeared in the Philosophical Transactions, No. 476, April, May, June, and July 1745, London, England. Pgs. 447-461.

Cefina, April 4. 1731- Read June 20, 1745.

The Countess Cornelia Bandi, in the 62d Year of her Age, was all Day as well as she used to be; but at Night was observed, when at Supper, dull and heavy. She retired, was put to Bed, where she passed three Hours and more in familiar Discourses with her Maid, and in some Prayers; at last, falling asleep, the Door was shut. In the Morning, the Maid, taking notice that her Mistress did not awake at the usual Hour, went into the Bed-chamber, and called her; but not being answer'd, doubting of some ill Accident, open'd the Window, and saw the Corpse of her Mistress in this deplorable Condition. Four Feet Distance from the Bed there was a Heap of Ashes, two Legs untouched, from the Foot to the Knee, with their Stockings on; between them was the Lady's head; whose Brains, Half of the Backpart of the Scull, and the whole Chin, were burnt to Ashes; amongst which were found three Fingers blacken'd. All the rest was Ashes, which had this particular Quality, that they left in the Hand, when taken up, a greasy and stinking Moisture. The air in the Room also observed cumbered with Soot floating in it: A small Oil-Lamp on the Floor was cover'd with Ashes, but no oil in it. Two Candles in Candlesticks upon a table stood Upright; the-Cotton was left in both, but the Tallow was gone and vanished. Somewhat of Moisture was about the Feet of the Candlesticks. The Bed receiv'd no Damage; the Blankets and Sheets were only raised on one Side, as when a Person rises up from it, or goes in: The whole Furniture, as well as the Bed, was spread over with moist and ash colour Soot, which had penetrated into the Chest-of-drawers, even to foul the Linnens: Nay the Soot was also gone into a neighbouring Kitchen, and hung on the Walls, Movables, aid Utensils of it. From the Pantry a Piece of Bread cover'd with that Soot, and brown black, was given to several Dogs, all which refuse to eat it. In the Room above it was moreover taken notice, that from the lower Part of the Windows trickled down a greasy, loathsome, yellowish Liquor and thereabout they smelled like a Stink, without knowing of what ; and saw the Soot fly around. It was remarkable, that the Floor of the Chamber was so thick smear'd with a gluish Moisture, that it could not be taken off; and the Stink spread more and more through the other Chambers. It is impossible, that, by any Accident, the Lamp should have caused such a Conflagration. There is no Room to suppose any supernatural Cause. The likeliest cause then is a Flash of Lightning; which, according to the most common Opinion, being but a sulphurous and nitrous Exhalation from the Earth, having been kindled in the Air, did penetrate either thro' the Chimney, or thro' the Chinks of the Windows, and did the Operation. All the above mentioned Effects prove the Assertion; for those remaining foul Particles are the grossest Parts of the Fulmen, either burnt to Ashes, or thickened into a viscous bituminous Matter. Hence no Wonder the Dogs would not eat of the Bread, because of the Bitterness of the Soot, and Stink of the Sulphur that lodged on it. The impalpable Ashes of the Lady's Corpse are also a Demonstration; for nothing but a Fulmen could produce such an Effect. They say that there was not any Noise; but maybe there was, and they heard it not, being in a found Sleep: Besides, there have been seen Lightnings and Fulmina without Noise; as one may very often observe. THIS is the whole Narration; after which I think proper to place what is said in the Preface relating to it. In the Acta Medicia & Philsophica Hafnienfia, published by the celebrated Thomas Bartolin, 1673. Vol. II. page 211. n. 118. one may see such another Accident related in these very Words. "A poor Woman at Paris used to drink Spirit of Wine plentifully for the Space of three Years, for as to take nothing else. Her Body contracted such a combustible Disposition, that one Night she, lying down on a Straw-Couch, was all burned to Ashes and Smoke, except the Scull, and the Extremities of her Fingers." John Henry Cohausen relates this Fact in a Book printed at Amsterdam 1717, intituled, Lumen novum Phosphoris accensum; and in the fifth Part, p. 92. relates also, "That a Polish Gentleman, in the Time of the Queen Bona Sforza, having drank two Dishes of a Liquor called Brandy-Wine, vomited Flames, and was burnt by them." Source: Philosophical transactions, giving some accompt of the present undertakings, studies and labors of the ingenious in many considerable parts of the world , Volume 43, Issues 475-477 edited by John Martyn ((Londres)), James Allestry ((Londres)), Henry Oldenburg (Published: London : printed by T. N. for John Martyn ... and James Allestry, printers to the Royal-Society, 1668 |

|

An Account of a Woman accidentally burnt to death at Coventry. By B. Wilmier, Surgeon, at Coventry. In a Letter to Mr. William Sharpe. From the Philosophical Transactions S I R, THE following case, which has lately engaged the attention of every one in this part of the world, appears to me so very extraordinary, that I was determined to give you a minute account of its circumstances; which will be the more agreeable to you, as you may depend upon the truth of every thing that I shall relate to you concerning it. Mary Clues, of Gosford-street, in this city, aged 52 years, was of an indifferent character, and much addicted to drinking. Since the death of Her husband, which happened about a year and a half ago, her propensity to this vice increased to such a degree, that, as I have been informed by several of her neighbours, she has drank the quantity of four half pints of rum, undiluted with any other liquor, in a day. This practice was so familiar to her, that scarce a day has passed this last twelvemonth, but she has swallowed from half a pint to a quart of rum or aniseed water. Her health gradually declined; and, from being a jolly, well-looking woman, she grew thinner, her complexion altered, and her skin became dry. About the beginning of February last, she was attacked with the jaundice, and took to her bed. Though she was now so helpless, as hardly to be able to do any thing for herself, she continued her old custom of dram-drinking, and generally smoked a pipe every night. No one lived with her in the house. Her neighbours used, in the day, frequently to come in, to see after her ; and in the night, commonly, though not always, a person sat up with her; to whom she has often cried out, that she saw the devil in some part of the room, who was come to take her away. Her bedroom was next the street, on the ground floor, the walls of which were plastered, and the floor made of bricks. The chimney is small, and there was a grate in it, which, from its size, could contain but a very small quantity of fire. Her bed-head stood parallel to, and at the distance of about three feet from the chimney. The bed's head was close to the wall. On the other fide the bed, opposite the chimney, was a window opening to the street. One curtain only belonged to the bed, which was hung on the side next the window, to prevent the light being troublesome. She was accustumed to lie upon her side, close to the edge of the bedhead, next the fire; and on Sunday morning, March the 1st, tumbled upon the floor, where her helpless slate obliged her to lie some time, till Mary Hpllyer, her next neighbour, came accidentally to see her. With some difficulty she got her into bed. The same night, though she was advised to it, she refused to have anyone to sit up with her ; and, at half past eleven, one Brooks, who was an occasional attendant, left her as well as usual, locked up her door, and went home. He had placed two bits of coal quite backward upon the fire in the grate, and put a small rush-light in a candlestick which was set in a chair, near the head of the bed but not on the side where the curtain was. At half after five the next morning, a smoke was observed to come out of the window in the street; and, upon breaking open the door, some flames were perceived in the room, which, with five or fix buckets of water, were easily extinguished. Betwixt the bed and fire-place lay the remains of Mrs. Clues. The legs and one thigh were untouched. Except these parts, there were not the least remains of any skin, muscles, or viscera. The bones of the skull, thorax, spine, and the upper extremities were completely calcined, and covered with a whitish efflorescence. The skull lay near the head of the bed, the legs toward the bottom, and the spine in a curved direction, so that she appeared to have been burnt on her right side, with her back next the grate. The right femur was separated from the acetabulum of the ischium; the left was also separated, and broken off about three inches below the great trochanter. The connection of the sacrum with the ossa innominata, and the inferior vertebrae of the loins were destroyed. The intervening ligaments kept the vertebrae of the loins, back, and neck together, and the skull was still resting upon the atlas. When the flames were extinguished, it appeared that very little damage had been done to the furniture of the room, and that the side of the bed next the fire had suffered most. The bedhead was superficially burnt, but the feather bed, sheets, blankets, etc. were not destroyed. The curtain on the other side of the bed was untouched, and a deal door, near the bed, not in the least injured. I was in the room about two hours after the mischief was discovered. I observed that the walls and every thing in the room were coloured black : there was a very disagreeable vapor; but I did not observe, that anything was much burnt, except Mrs. Clues; whose remains I saw in the state I have just described. I took away one of the bones (the remains of the sacrum) which you have inclosed with this letter. The only way that I can account for it, is, by supposing that she again tumbled out of bed on Monday morning, and that her shirt was set fire to, either by the candle from the chair, or a coal falling from the grate ; that her solids and fluids were rendered inflammable, by the immense quantity of spirituous liquors she had drank, and that when she was set fire to, she was probably soon reduced to ashes, for the room suffered very little. B. WlLMER. Coventry-, April 9, 1772. Source: The Annual Register: Or a View of the History, Politics and Literature, for the year 1775., published in London, 1776 ; appeared originally on The Philosophical Transactions, Vol. LXIV, Part II, 1774 London, England. Pgs. 340-343. |

|

...He remarks that some facts of this kind were known at an early period; and that (among other writings on the subject) M. René Moreau, (a physician of Paris) published a letter in 1644, in which he speaks of a flame that issued from the stomach of a woman, who died at Lyons; which flame he considers to be of the same nature as the ignis lambeus, of which Virgil speaks, in the second book of the Eneid, line 683: Ecce levis summo de vertice visus Iuli fundere lumen apex, tactuque innoxia mollis lambere flamma comas et circum tempora pasci. From the instances which he gives of human

combustion, we shall select those which we have not already detailed. |

|

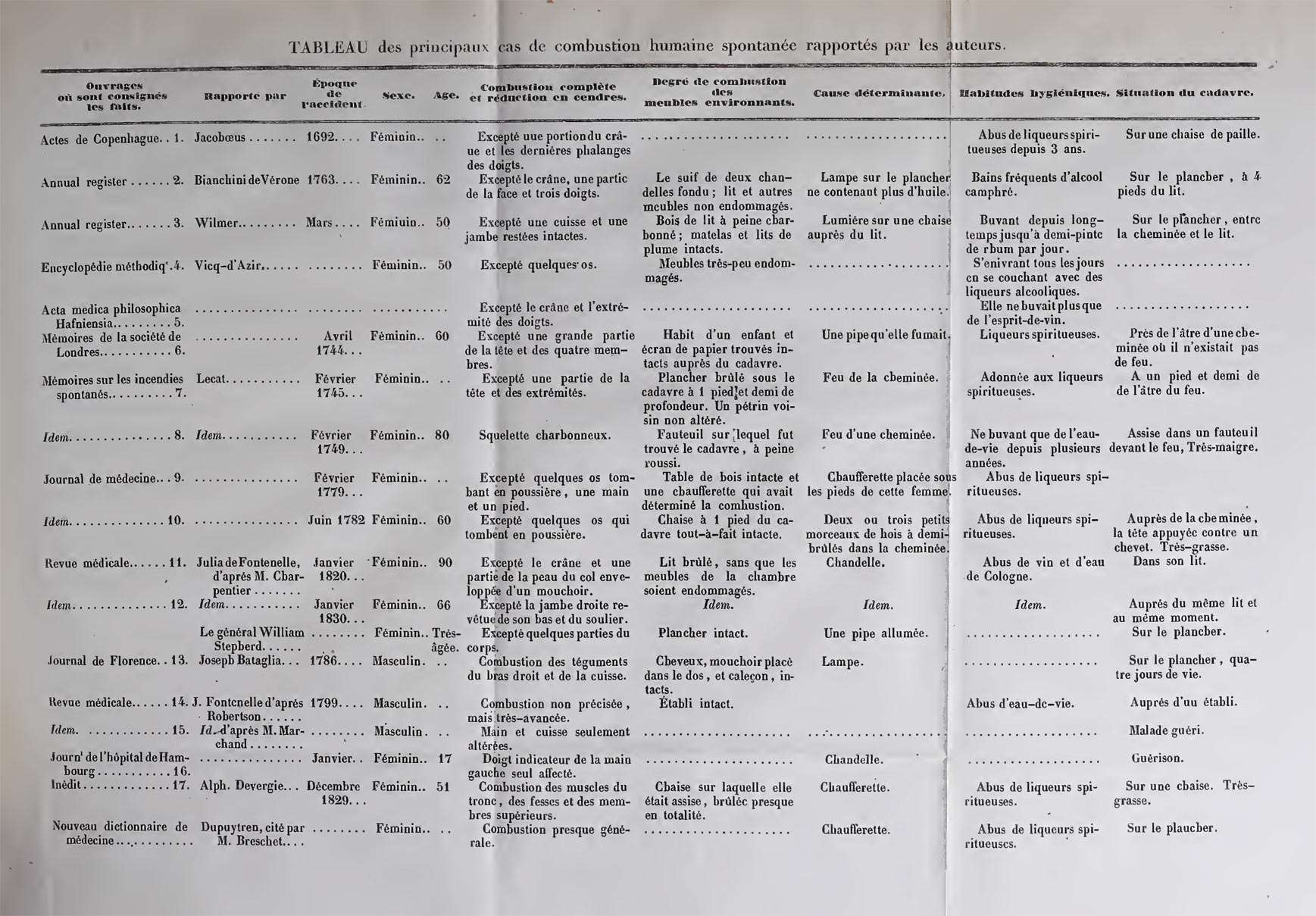

The following is a publication from 1841. It shows that spontaneous human combustion was well known at that time, and that some people had already investigated many cases and had found unusual characteristics that showed up in most cases. Source: Thèse présentée et publiquement soutenue à la Faculté de médecine de Montpellier, le 1er février 1841 by Royal College of Surgeons of England, page 32 {original French text at the end of this chapter) I will not discuss here the various theories that have been issued on spontaneous combustion; I only deal with this issue in respect of forensic medicine: this question studied in this way is even more interesting, an ignorant doctor could lead innocent people to the scaffold, or at least expose them to undergo a judgment, as has already been done. Nowadays the authors agree more or less that the use of alcoholic beverages is a predisposing cause of spontaneous combustion, especially for people in whom the abuse of these liqueurs produced polysarcia [=excess fat]; However, it was noticed that in a few rare cases spontaneous combustion happened in slender subjects. Women are more likely than men to spontaneous combustion, which is explained by women have more soft tissues, and that they are more probe to the accumulation of gases, and that women take it to a habit to be more passionate than men. This accident happens more often in older people than younger, which is explained further because young people have other passions that outweigh that of spirits. The flame that occurs in spontaneous combustion is light blue, motionless; it is useless to pour water on it, at times it even seems to animate the fire; so that combustion does not stop until the body parts have been reduced to charcoal or ashes. Rarely all parts are destroyed; part of the extremities often remain, sometimes also vertebrae; but the soft parts are often completely burned. When the body is completely consumed, the amount of ash is so small, that it is not in proportion to the volume of the body. In general, furniture around the body, and sometimes even the clothes that covered the body, are not damaged; but they are covered with a layer of wet and greasy soot, and in the apartment one can smell a very foul empyreumatic odor. The spontaneous combustion occurs most often during the winter. I also thought to borrow the table from the dictionary in 15 volumes of M. Alph. Devergie, which gives the most important cases of spontaneous combustion. |

This is the table accompanying the article:

Sixth and seventh column of the above page:

|

Complete combustion and reduction to ashes.

Except a portion of the skull and the bones of the fingers.

|

The degree of combustion of the surrounding furniture Tallow of two candles melted; bed and other furniture undamaged.

|

|

Some cases mentioned in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 1836 On Spontaneous Combustion — From an Essay Read at the Last Annual Meeting of the Med. Society of Tennessee JAMES OVERTON, M.D. Boston Med Surg J 1835 (in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Volumes 13-14, 1836)

In 1725, the wife of a man by the name of Millet perished as the victim of spontaneous combustion, in the city of Rheims, in France. Her remains were found in the kitchen, at the distance of a foot or foot and a half from the chimney. Some portions of the bones of the head, of the extremities, and some the dorsal vertebrae, had alone escaped entire incineration. Millet owned or possessed a maid servant, who was young, and remarkable for her extraordinary beauty; and disreputable and alarming suspicions were soon started against him. Millet was subjected to all the rigors of a criminal prosecution, and finally convicted and condemned to be execution for the murder of his wife. He took an appeal from this decision, and, arraigned before a more enlightened tribunal, the case was ascertained to be one of "spontaneous combustion," and Millet consequently escaped at once from the horrors of the scaffold and the odium of having been the murderer of his own wife.

The room where this spontaneous combustion had occurred was filled with a humid soot, of the color of ashes; it had penetrated the texture of her curtains, and stained her bed linen. Source: The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Volumes 13-14, page 22-23 |

|

This is the original French text of Thèse présentée et publiquement soutenue à la Faculté de médecine de Montpellier, le 1er février 1841 by Royal College of Surgeons of England, page 32 Je ne discuterai pas ici les différentes théories qui ont été émises sur la combustion spontanée ; je traiterai seulement cette question sous le rapport de la médecine légale : cette question , étudiée de cette manière , est d’autant plus intéressante, qu’un médecin ignorant pourrait conduire à l'échafaud des personnes innocentes, ou tout au moins les exposer à subir un jugement, comme cela s’est déjà présenté. Les auteurs sont aujourd’hui à peu près d’accord que l’usage des boissons alcooliques est une cause prédisposante de la combustion spontanée, surtout pour les personnes chez lesquelles l’abus de ces liqueurs a produit ta polysarcie ; cependant on a reconnu quelques cas rares , il est vrai , de combustion spontanée chez des sujets maigres. Les femmes sont plus exposées que les hommes aux combustions spontanées, ce qui s’explique assez parce que les femmes ont les tissus plus lâches et plus propres aux accumulations gazeuses, et que, lorsque les femmes prennent une habitude, elles s’y livrent avec beaucoup plus de passion que les hommes. Cet accident arrive plus souvent chez les personnes âgées que chez les jeunes, ce qui s’explique encore parce que les jeunes personnes ont d’autres passions qui l’emportent sur celle des boissons spiritueuses. La flamme qui se produit dans les combustions spontanées est légère , bleuâtre, immobile; l’eau que l’on jette dessus est inutile pour l’éteindre, elle semble même quelquefois l’animer ; de sorte que la combustion ne s’arrête guère que lorsque les parties sont charbonnées ou réduites en cendres. Rarement toutes les parties sont détruites; il reste presque toujours une partie des extrémités, quelquefois des vertèbres; mais les parties molles sont souvent entièrement brûlées. Lorsque le corps est complètement consumé, la quantité de cendre est si petite, qu’elle n’est nullement en proportion avec le volume du corps. Ordinairement les meubles qui environnent le cadavre, et même quelque- fois les vêtements qui le recouvraient, ne sont pas endommagés; mais il se dépose à leur surface une couche de suie humide et grasse, et, dans l’appartement, on respire une odeur empyreumatique très-fétide. Les combustions spontanées ont lieu le plus souvent pendant l’hiver. J’ai cru devoir emprunter au dictionnaire en 15 volumes le tableau de M. Alph. Devergie, dans lequel sont cités les principaux cas de combustions spontanées.

|